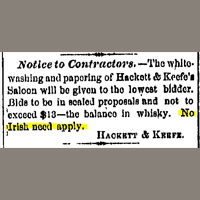

In 2002 a professor from the University of Illinois proposed the theory that during the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, the Irish labor force wasn’t nearly as discriminated against as prevailing theories led us to believe. He suggested that the help wanted advertisements that businesses put up in their windows and the notices that businesses placed in the paper, both of which clearly stated “No Irish Need Apply,” were actually extremely rare and primarily a myth.

So a debate arose, as these things do among academics, with many objecting to that conclusion and a few agreeing. It must be said that this was a fairly under-the-radar kind of debate, since most of us are not academics and only a tiny percentage of academics are students of 19th century Irish-American history. But to be fair, the subject was hard to research in any quantifiable way in 2002.

In 2015, an eighth grader using Google searches proved the professor spectacularly wrong. Since so many print pieces such as newspapers have been digitized since 2002, it is fairly easy to do this kind of research and to discover these patterns in 2015. She found that the phrase “No Irish Need Apply” came up pretty frequently in newspaper “help wanted” ads across the country during this time period. She found fifteen such ads in the New York Sun newspaper in 1842 alone, and that was well before many Irish immigrants came to the United States.

Of course, immigrant Jews, Italians, Germans, Poles, Chinese and many others were just as discriminated against, along with enslaved and non-enslaved blacks, and undoubtedly the same kind of search would produce similar results. Further, there are many editorial cartoons and illustrations that are quite clear on the subject of immigration. Many are incredibly xenophobic and almost all echo many of the sentiments that seem to dominate the political landscape today: “they are taking our jobs,” “they should speak English,” the country of origin is kicking out “thieves, liars, murderers, anarchists, Bolsheviks, communists,” etc. Sound familiar? The rhetoric hasn’t really changed in the last 150 years.

The irony, and perhaps a happy ending of a sort, is that from being one of the most discriminated-against and reviled immigrant groups in the United States in the mid-19th century, some would argue the Irish are almost venerated now. We admire New York City firefighters, especially post 9/11, many of whom were Irish in the early days of firefighting in New York and many are of Irish descent now. And we absolutely adore St. Patrick’s Day, which is as much a celebration of being Irish as it is an excuse for drinking vast quantities of green beer.

What changed? Was it just time wearing away the rough edges of discrimination against this group? Was it because the Irish were elected into political positions and influenced outcomes? Was it because attention was diverted to other immigrant groups or peoples with customs, cultures and skin colors different from prevailing groups? Maybe the answer lies in all three.

The beauty is that as long as original digital and digitized written sources stay in the public arena, scholars and students fifty years from now will be able to run the same kinds of searches and discover what kinds of patterns of rhetoric prevail in our current social, economic and political arena. Will the same ethnic groups continue to crop up or will it be different groups? What will be the agent of change?